This entry was posted on miércoles, marzo 31st, 2010 at 20:07 and is filed under Estudio comparativo de los pastizales de la Cordillera Cantábrica y del Sistema Central . Tesis Doctoral Matías Mayor 1965. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

High Nature Value farming

……………

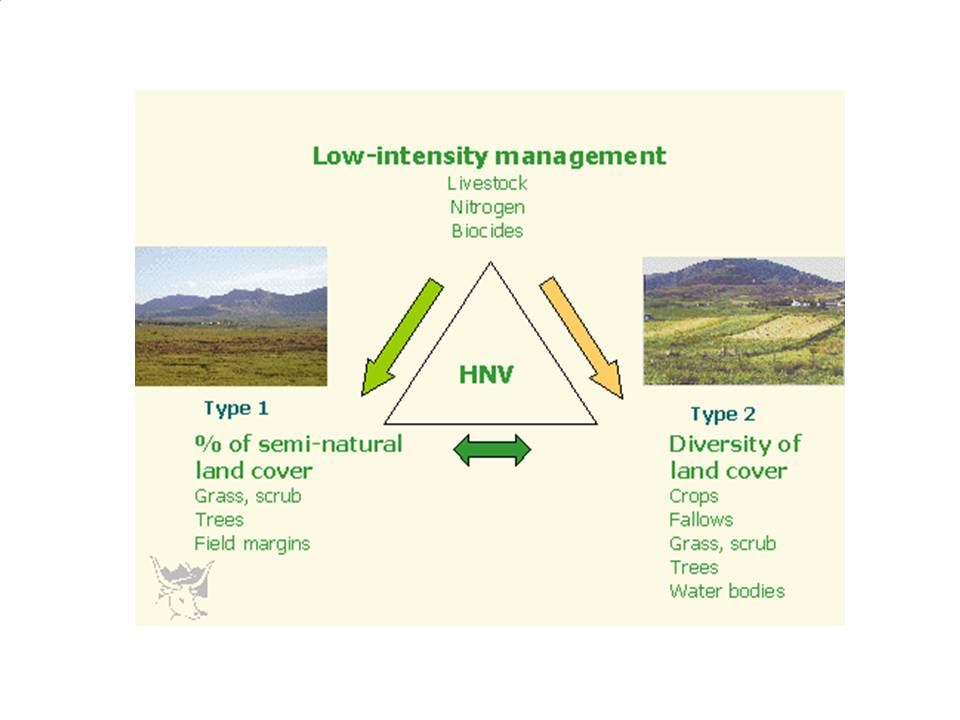

The broad types of High Nature Value farming (European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism)

HNV farming is characterised by a combination of:

- Low intensity of land use

- Presence of semi-natural vegetation

- Presence of a landscape mosaic

The following diagram illustrates the interplay between these criteria. The dominant characteristic of HNV farming is the low-intensity use of the land and of other factors of production (except for labour and traditional knowledge). Also essential is a significant presence of semi-natural vegetation on the farmed area. In some situations, the semi-natural vegetation is found in a mosaic with low-intensity arable and/or arable crops.

————————————

…………………………………

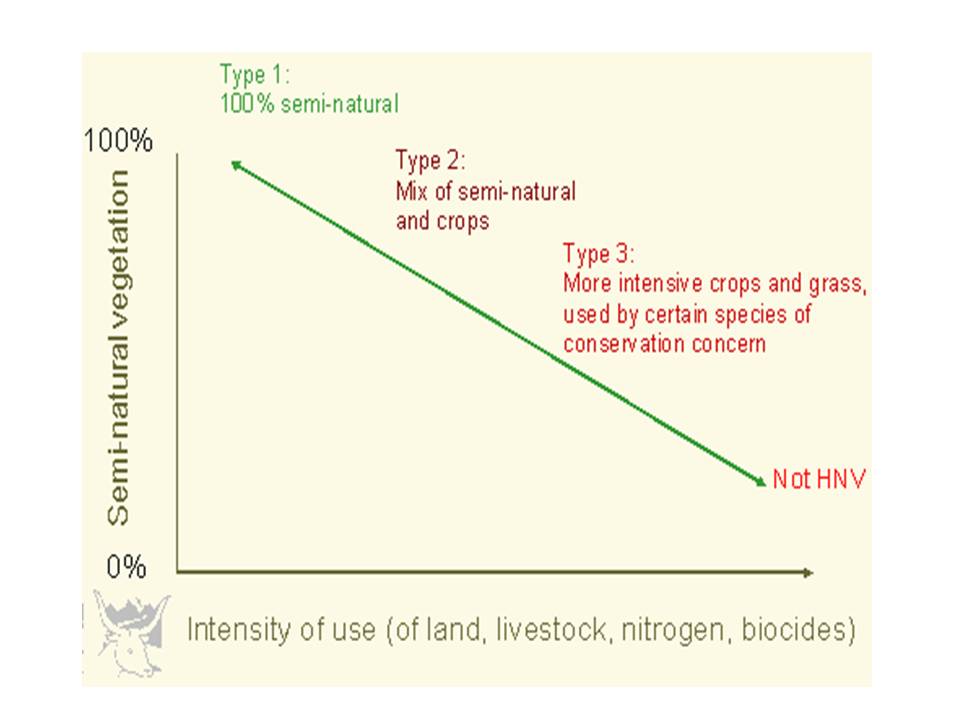

Type 1 HNV farmland

The most widespread type of HNV farmland consists of semi-natural vegetation under low-intensity use for livestock raising. The grazed semi-natural vegetation may be grassland, scrub or woodland, or a combination of different types. Farmland that is predominantly grazed semi-natural vegetation has been labelled as Type 1 HNV farmland (Andersen et al, 2003).

Often the semi-natural grazing is not part of the farm holding, but has some other ownership (common land, State land etc.), so it is important not to consider only the UAA within the holding when identifying HNV farmland.

HNV livestock farms will usually have more than one type of forage land. This can range from the least altered semi-natural vegetation (never tilled, sown or fertilised), through grasslands that may be occasionally tilled and/or lightly fertilised, to more productive or “improved” pastures, and cereal crops for fodder. Although more productive, these fields are still managed at low intensity compared with mainstream farming. They can be an important part of an HNV farming system, and can also contribute to nature value when combined with a sufficient area of semi-natural grazing, by providing feeding opportunities for wildlife, and hosting certain plant communties that have become rare in more intensive farming landscapes.

Determining which pastures are semi-natural, and which are not, is to some extent a value judgement. One approach is based on the presence of certain indicator species, another is to decide that a pasture that has not been resown or fertilised for 20 years (for example) can be considered semi-natural. Occasional tillage may be compatible with semi-natural status. This is especially relevant in Mediterranean regions, where grasslands may be tilled occasionally for scrub control, without significantly reducing their natural value. Spontaneous vegetation in olive groves and on low-intensity fallow land may also be counted in the same category, if it is not affected significantly by fertilisers or biocides.

Only at the Member State or regional level can biodiversity significance of such thresholds and distinctions be established – the aim is to choose criteria which provide a good differentiation between HNV farmland and farmland of lower nature value. In practice, there is often no clear dividing line between semi-natural and artificial pasture. In some cases, it may be appropriate to consider a category of “nearly semi-natural” pasture, between the semi-natural and the “improved” or “intensified” pasture.

The fact that the vegetation is grazed by livestock (or mown for hay) is important, as this confirms that it is part of a farming system. This is not necessarily grassland: scrub and forest are an important forage resource in some parts of the EU (especially southern and eastern regions), and should be recognised as farmland. However, semi-natural woodland that is not grazed should be considered as a separate, non-farming landuse. Semi-natural vegetation that is grazed primarily by wild herbivores, such as deer (e.g. estates on moorland in Scotland or dehesas in Spain which are kept exclusively or mainly for hunting), should not be counted as HNV farmland.

Type 2 HNV farmland

Farms and landscapes with a lower proportion of semi-natural vegetation, existing in a mosaic with arable and/or permanent crops, can also be of high nature value. Nature values will tend to be higher when the cropped areas are under low-intensity use, providing a mix of habitats that are used by a range of wildlife species, with numerous and complex species flows (invertebrates, birds, mammals and reptiles). This type of HNV farmland has been labelled Type 2. Because the proportion of land under semi-natural vegetation is less than in Type 1, and the proportion of cultivated land is greater, the management of the latter and existence of an “ecological infrastructure” of landscape features, are especially critical for wildlife. More intensive use of the cultivated land, and the removal of features, will lead to a rapid decline in wildlife values.

Peripheral semi-natural features, such as hedges, other field-margins and trees, are often found on Type 2 HNV farmland. These provide additional habitats and will tend to increase nature value. However, their total surface area is usually small compared with the productive area, so that it is the characteristics of the latter which determine whether the farmland in question is HNV. Peripheral features alone are not sufficient.

Type 3 HNV farmland

At the more intensive end of the HNV spectrum are farmland types whose characteristics of land cover and farming intensity do not suggest HNV farming, but which nevertheless continue to support species of conservation concern. Generally these are bird populations. This has been labelled Type 3 HNV farmland.

The three types of HNV farmland are not intended to be precise categories, with a sharp boundary between them. Rather, they should be seen as a continuum, ranging from those with a higher proportion of semi-natural vegetation and lower intensity use (Type 1) to more intensively managed farmland that still supports certain species of conservation value (Type 3). See below.

…………………………..

……………………