This entry was posted on martes, mayo 4th, 2010 at 21:13 and is filed under Estudio comparativo de los pastizales de la Cordillera Cantábrica y del Sistema Central . Tesis Doctoral Matías Mayor 1965. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.

Traditional land-use systems:sustainability,efficiency and biodiversity.Land management

………………………………………….

La PAC (Politica Agrícola Comunitaria), trata de buscar un equilibrio entre los sectores conservacionistas o ambientalistas de UE y los sectores de la producción y el mercado. Está claro que han conseguido avances notorios entre ambas partes.Un ejemplo lo tenemos en haber conseguido de la PAC el desacoplamiento, total o parcial, de las ayudas: su desvinculación a la producción.

Desacoplamiento es una ayuda que se abona independientemente de que el agricultor produzca o no .

Este pago está sujeto al cumplimiento de la condicionalidad: buenas condiciones agrarias y medioambientales y requisitos legales y de gestión

EL Foro Europeo para la conservación de la naturaleza y el pastoralismo (EFNCP), está manteniendo una actitud muy positiva sobre la conservación de la Naturaleza, quizá aunque parezca sorprendente mucho mayor que Natura 2000.

No dejó de sorprenderme el comentario sobre la falta de entendimiento entre los defensores de LIC (Lugares de interés comunitario de Red Natura 2000 y HNV (Los altos valores naturales) de las granjas agrícolas,aunque ambos persigan fines proteccionistas.De tal forma que se critica a Natura 2000, por un excesiva preocupación por la conservación de Hábitats muy selectivos y olvida los demás.

El foro europeo para la conservación de la naturaleza y el pastoralismo ( EFNCP) mantiene que en las tierra de cultivo con baja intensidad (Low-intensity farming systems),hay muchas especies que se deben proteger y no hay regulación ninguna.

Yo creo que todo el montaje de Natura 2000, en algunos Países de la U.E, ha quedado en una serie de formalidades, que son muy dificil de cumplir, entre otras cosas por carecer de presupuesto económico. Conocemos el peligro de amenaza de una especie pero somos impotentes para tomar medidas eficaces para detener la amenaza.

Los monitores, que fiscalizan la posible degradación de los LIC, deben estar preparados, no solo en lo técnico sino en lo científico y no es fácil conseguirlo sin pagarlo bien.

Tengo un ejemplo de la sociedad Española para el Estudio de los pastos, que le daban una cantidad irrisoria de dinero para comprobar el estado de los cervunales del Norte de España.En mi opinión, se estaban rellenando unos formularios, sin salir al campo desde el despacho, sin valor niguno.

…………………………………………………………………..

………………………..

………………..

…………………..

……………….

…………………………….

……………………..

…………………

…………………………………..

……………………………………………..

…………………….

………………………………………………………..

…………………….

…………………………

………………………….

…………………………………

……………………..

…………………………………

Bibliografía

Colin Hindmarch & Mike Pienkowski .2000.Land Management the

hidden cost .

………………..

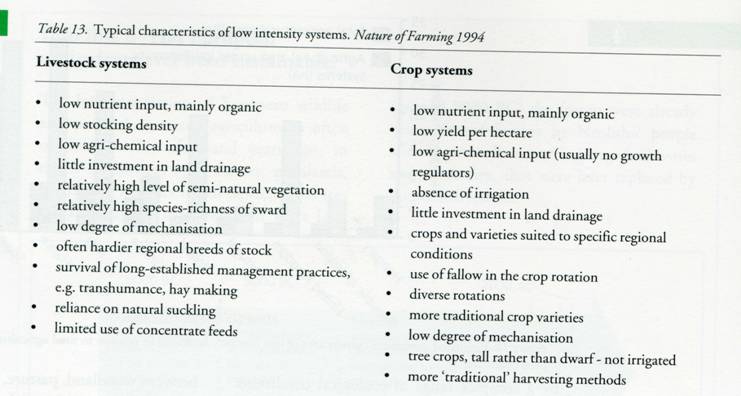

The nature conservation value of low-intensity farming systems

Mike Pienkowski

European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism

The European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism

Europe’s natural and cultural heritage is enriched by the wide variety of regional farming systems which work in harmony with local environmental conditions. However, many of these farming systems are currently under threat. The aims of the European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism are therefore:

- To increase understanding that certain European farming systems are of high nature conservation and cultural value.

- To ensure the availability, dissemination and exchange of supporting information, combining research and practical expertise.

- To bring together ecologists, nature conservation managers, farmers and policy makers to consider problems faced by these systems and potential solutions.

- To develop and promote policy options which ensure the ecological maintenance and development of these farming systems and cultural landscapes.

The Forum is a pan-European non-profit organisation. It is a network to exchange information, identify conclusions, and inform policy development. To achieve its aims, the Forum holds conferences every two years, organises workshops and seminars, and produces two issues of the newsletter La Cañada per year. It also conducts research into the ecological relationships on high-nature-conservation-value farmland and into the development of appropriate policies for such areas.

One of the Forum’s means of making its work available to policy-makers is the series of seminars held in Brussels. These involve both NGO and governmental/Commission personnel, and are particularly noted for bringing together people working at European policy levels and those farming and managing land for conservation on the ground.

The research work that the Forum has undertaken to underpin this work has included:

- the initial identification and classification of low-intensity farming systems in nine European countries (Beaufoy et al. 1994; Bignal 1998), and the production of popular posters (Bignal et al. 1994)

- detailed ecological studies on the ways in which certain species depend on farming operations (e.g. Bignal & Curtis 1989; Bignal & McCracken 1993, 1996; Bignal et al. 1997)

- analyses of the interactions between natural systems, farming practice and agricultural policy (e.g. Beaufoy 1997, 1998; Bignal et al. 1996; Galbraith & Pienkowski 1990; Goss et al. 1997; Mitchell 1996; Mitchell et al. 1997; Pain & Pienkowski 1996; Pienkowski & Bignal 1993, Pienkowski et al. 1995; Tubbs 1997).

The ecological context of European agriculture

If we think of them at all, we tend to consider sustainable land-use and the conservation of biodiversity as relating to tropical rainforests or the plains of Africa, rather than to most of Europe. However – until relatively recently – Europe was a region in which people were a closely integrated part of the sustainable system. Developments had taken place gradually over long periods so that human use and wildlife had developed alongside each other.

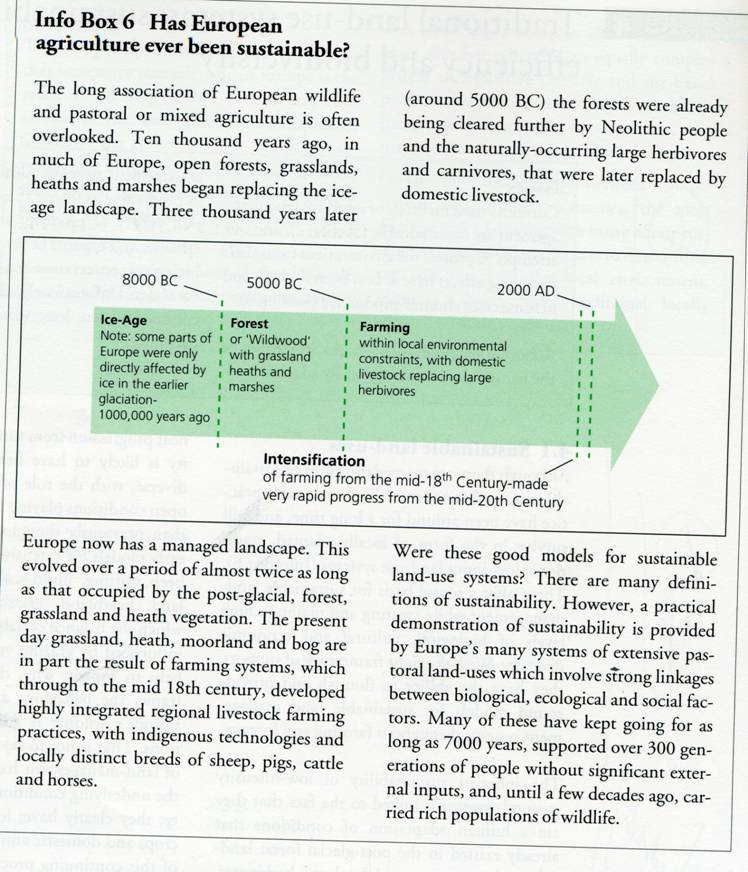

The long association of European wildlife and pastoral or mixed agriculture is often overlooked. Ten thousand years ago, forest began replacing the Ice Age landscape.

After only three thousand years (around 5000 BC) the forests were already being cleared by Neolithic people. It is interesting to note that this agricultural landscape evolved over a period twice as long as that occupied by the post-glacial forests. Much of Europe is essentially a managed landscape – and its grasslands, heaths, moorlands and bogs together with the present day associated wildlife are partly the result of farming systems. From the Dark Ages – and probably much earlier – through to the mid 18th century, a highly developed and integrated regional livestock farming system evolved, with distinct local breeds of sheep, pigs, cattle and horses (see also Tubbs 1997).

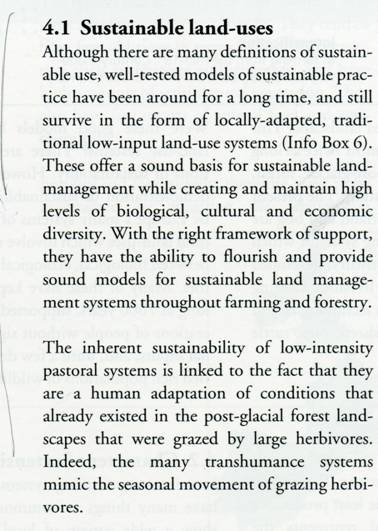

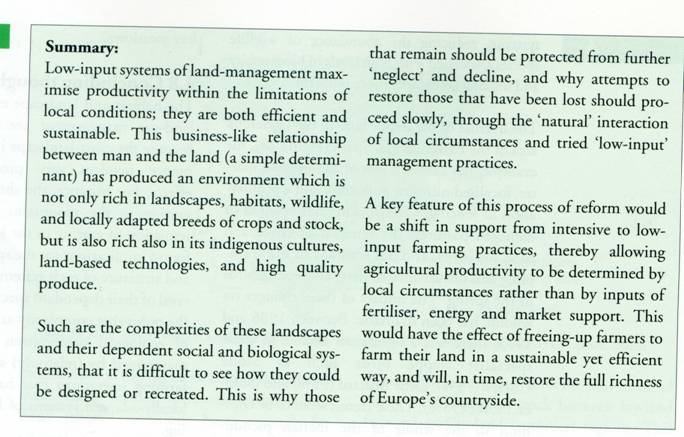

How do we know that these systems were environmentally sustainable? There are many definitions of environmental sustainability. However, some of these systems have kept going, with developments, for 7000 years, supporting over 300 generations of people without significant external inputs. Such systems also supported, at least until the last few years, rich populations of wildlife. If anything I plan lasts a fraction of that time, I would dare to claim – if I were still around – that it was sustainable.

Human communities modified the landscape into a wide variety of farming systems, some of which survive (Beaufoy et al. 1994; Bignal 1998; Bignal et al. 1994). The interaction of grazing and climate considerably modified the plant communities of heathland, grassland, mountain and steppe which sustained the pastoralism, contributing to the survival and prosperity of local communities. Farm systems varied in response to local and regional conditions, but their common characteristics were that they were low input, low output, usually labour intensive, and economically and ecologically sustainable. These farm systems have enriched Europe’s open ground flora and fauna by enhancing diversity of habitat, such as around settlements, whilst maintaining the large scale open habitats. The pastoral exploitation of mountain regions could be accomplished only by transhumance, leading to the development of long distance drovers’ roads which came to possess peculiar floras arising from seasonally extremely intensive grazing. Another kind of drovers’ road, that led from regions of production to large city markets, such as those from Wales and northern Britain to London, were presumably equally rich, but these are almost completely lost to us now. Those areas of environmentally sustainable farming that survive tend to have high nature value.

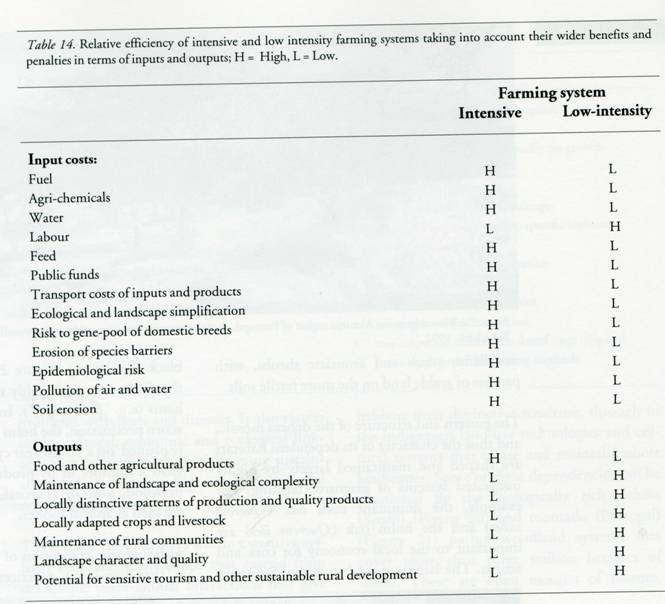

The essential characteristics of high biodiversity rural land uses are that external energy inputs are low. Inevitably, as a result, outputs per unit area are also low. This does not mean that efficiency is low; generally, it is rather high.

In the second half of the 20th century, there has been a new kind of disruption in the European ecosystem which has involved a massive decline in biodiversity. Wildlife had been able to adjust and exploit the earlier agricultural situations because modifications to the environment had been gradual. However, in the last century and particularly in recent decades, this has changed. Modern machinery and agro-chemicals allow rapid changes to the farmed environment over huge areas, to impose a high-input, standard, factory landscape over the previous characteristic regional features.

There are many costs to Society of these changes, but the range of these impacts is often overlooked. One of the major costs is to wildlife. This is important in itself, but also provides some measure of the degree of sustainability of our actions.

Some of the best monitoring data are for birds (Pain & Pienkowski 1996; Tucker & Heath 1994). For example, skylark Alauda arvensis populations are declining throughout the western half of Europe. The eastern populations are expected to follow if we continue to «aid» eastern European farming in the ways we seem to be doing. Other species have already gone. The corncrake Crex crex was a common feature of farmland throughout Europe until earlier this century, as is well attested in popular stories and poetry. It is declining throughout Europe. In the British Isles, its progressive restriction to a few Hebridean islands and parts of Ireland match well the introduction of mechanisation and tidy fields.

The intensification of agriculture has had other major impacts on both the human population and wildlife. The quantities of fertilisers used have increased markedly in recent decades. Much of this finds its way into the water supply. In 26 countries of Europe, the European Environment Agency has reported that groundwater pollution by nitrates, largely from agriculture, is a risk to human health problem. There have been similar increases in pesticide usage. The problem is even more widespread than for nitrates (Stanners & Bourdeau 1995).

I will not give examples of all the hidden costs to Society of the intensification of agriculture, especially as many were given in the Forum’s seminars (Mitchell 1996; Goss et al. 1998; Hindmarch et al. 1998). However, major costs have been identified in a range of aspects including:

- wildlife and habitats

- regionally adapted livestock breeds and mixtures

- employment & rural communities

- knowledge

- cultural identity and quality of life

- water supplies

- animal welfare and human health

- financial cost

Much of this intensification is driven by the structure of agricultural policies (see Goss et al. 1997; Goss et al. 1998; Beaufoy 1998). There are two global processes, which will impact this – and these changes could be very positive or negative for the environment. The World Trade Organisation negotiations will mean that payments for farming will soon be possible only for aspects, which do not distort the market. One of the few elements for which this is likely to be possible is for payments for the public good of nature conservation, soundly based on ecological work. Farming and nature conservation interests will need to develop even further their co-operation.

This links to the second global process. People throughout the world are increasingly concerned with a sustainable life-style and the conservation of biodiversity. For some, this relates to the quality of life. For others – whose home islands are likely to be drowned as a consequence of pollution and climate change – it is a matter of life itself. Politicians have taken these points on board, at least to the extent of reaching various treaties, such as those at Rio in 1992. The fulfilment of these commitments has been variable, but there are some signs that there is an increasing seriousness being attached to them.

The essence of the Convention on Biological Diversity is that wildlife cannot be conserved just tucked away in enclaves but its conservation depends on this being integrated in other land-uses (or sectors of human activity), whether these be agriculture, fisheries, transport, industry or whatever. This is intimately related to undertaking work in an environmentally sustainable way.

Article 6 of the Convention is particularly important in stressing the need to incorporate conservation into other policies and practices: each Contracting Party has committed itself [amongst other things] to:

b) Integrate, as far as possible and as appropriate, the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity into relevant sectoral or cross-sectoral plans, programmes and policies.

Turning to that formerly highly environmentally sustainable activity, farming, we can ask:

- Do more sustainable farming systems still exist?

- What policies do we need to maintain and restore environmentally sustainable farming systems?

- What practices on the ground do we need to maintain and restore these high-nature-value systems?

These three questions represent the focus of the Forum’s work.

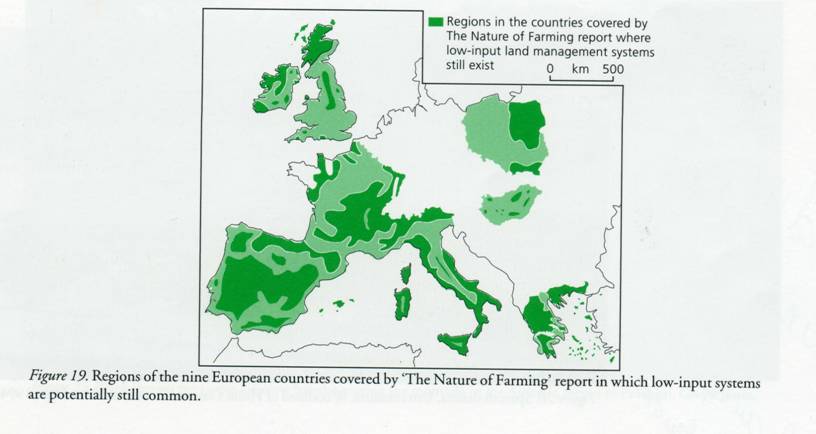

The European Forum on Nature Conservation and Pastoralism identified some years ago the need for information on where such farming systems of high nature value still exist (Beaufoy et al. 1994; Bignal 1998; Bignal et al. 1994). A collaborative study in 9 countries identified, classified and mapped the areas in which high-nature-value farming still occurs fairly commonly. Not surprisingly, there is a good general match between the areas in which high-nature-value farming remains and those where the water supply is least contaminated (see above).

Unfortunately, these high-nature-value areas are still being lost. And the many in central and eastern Europe are coming under increasing pressure to match the policies of western Europe.

Both conservationists and farming policy have tended to adopt the policy of single use. This is the very opposite of the concepts of sustainable use, adopted now by the EU and most countries around the world in the Convention on Biological Diversity.

………………….

Low-intensity farming systems in the conservation of the countryside

BIGNAL E. M. (1) ; MCCRACKEN D. I. ; 1996

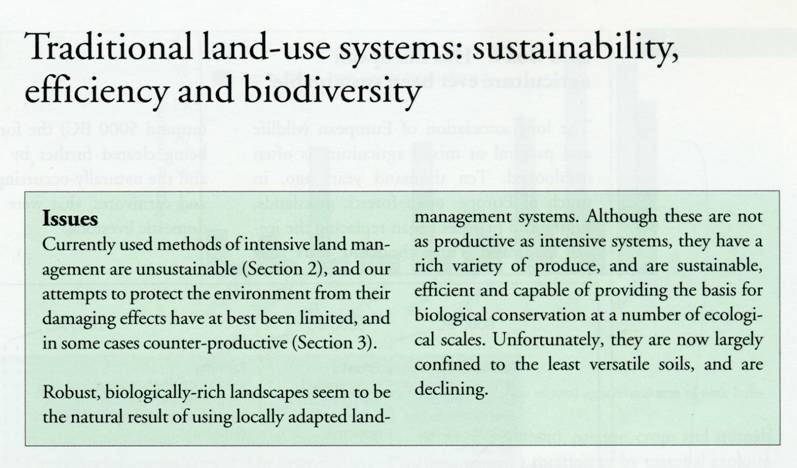

The historical role of agriculture in creating semi-natural vegetation is still not fully appreciated by many ecologists, conservationists, policy-makers or the general public. Nor is the fact that for many European landscapes and biotopes of high nature conservation value, the only practicable, socially acceptable and sustainable management involves the continuation of low-intensity farming. Consequently, too much emphasis is placed on attempting to ameliorate damaging effects of agricultural management rather than supporting ecologically sustainable low-intensity farming practices.

More than 50% of Europe’s most highly valued biotopes occur on low-intensity farmland. However, most of this farmland has no environmental policy directly affecting it; most management decisions are taken by farm businesses and determined primarily by European and national agricultural officials. As a result, there continues to be intensification or abandonment of traditional practices, changes which are equally damaging to the nature conservation value.

However, the nature conservation importance of low-intensity farming systems is gradually being recognized. Reforms and reviews of agriculture policy are providing a variety of potential opportunities for maintaining such systems. Unfortunately, initiating change through policy is a slow process. There is therefore also a pressing need to look for other opportunities to maintain surviving systems and, where poss-. ible, to reinstate those recently lost.

Although these systems may be considered low-intensity in terms of chemical inputs and productivity, they are usually high-intensity in terms of human labour. Therefore, the processes that make the low-intensity farmed countryside biologically rich and diverse must be understood, but at the same time mechanisms to make life easier and more rewarding for the people who work such farmland must be found.

Ecologists and conservationists should think less of’remnants of habitat being left amongst farmland’ and more of a farmland biotope for which optimum management practices need to be developed. At the same time the current emphasis on site-based conservation should be complemented by strategic initiatives that promote wise management of the wider countryside